An interview with Attilio Carducci

I met so many wonderful helpful people on my research trips to Catania and San Domino, but none more so than Attilio, who, despite our lack of a shared language, showed me around the island which has been his home all his life, and shared some of his memories of life on the island. Below is a summary of some of our conversations, which were made possible with the kind help of Vivien Williams who translated for us.

L-R My partner Matt, me, Attilio Carducci, Vivien Williams and Attilio’s daughter Claudia Carducci, outside Attilio’s house. (Much was made of Matt and Attilio’s extremely similar taste in footwear!)

Photo: Attilio Carducci

Watch: Attilio Carducci introduces himself and his family’s history on the Tremiti Islands

Attilio Carducci was born in 1927 on the Tremiti Islands. ‘My family are all from the Tremitis’ he told me. When he was a child, this was fairly unusual - attempts to encourage more Italian families to populate the islands had been largely unsuccessful.

We sat outside his house on one of the few residential streets on the island; one of three which stretch in a neat line from the central square. The area is labelled on maps as the ‘Villagio San Domino’.

‘It was my father who set up the village on this island’ Attilio says. ‘He went to Mussolini to get permission to build on the island. There were only three buildings on the island before him.

‘He went twice to Rome and families refused to come to the islands.’

It was more common at the time for people to reside on the neighbouring, larger island, San Nicola. In fact, Attilio told me, his was the only family living on San Domino.

‘My family created orchards and fields and crops. Now we have woodlands and pine trees but before everything was fields for growing food. And vineyards - we used to make wine that was 17 or 18 percent!’

Attilio’s father was the local fascist representative, but his training was in agriculture.

‘When my father was 16, he left the islands and lived in the province of Bari, where he studied agriculture, specifically vines. In Bari, Sicily and Calabria there was an epidemic, and he was called to cure the vineyards in these three regions. There’s a street in Andria named Carducci, and a school of agriculture dedicated to him.’

A young Attilio in the arms of a prisoner - possibly one of those imprisoned for their membership of the Sicilian mafia (Photo: Attilio Carducci)

‘For me, it was the excitement of seeing who was going to come next’

Attilio’s early life was dominated by the coming and going of strangers - the prisoners who were sent to the Tremiti islands for a variety of reasons during the fascist era. As a young child, it was an opportunity to encounter a extraordinarily diverse range of people.

‘For me, it was the excitement of seeing who was going to come next.

‘On San Nicola were the political prisoners, people who opposed fascism. On San Domino, first you had prisoners from the Sicilian mafia, then the homosexuals. After the homosexuals you had the war prisoners, and they could be fairly important people, big names in politics for instance. After that, you just had ordinary prisoners, engineers or any ordinary kind of person who had opposed fascism and so Mussolini had them sent here. They stopped coming at the end of the war.

‘There was barbed wire all over the place, all the buildings were surrounded by barbed wire, and every 100 metres or so you had a guard, and during the night you would hear alarms from the guards.

‘Life used to be very different. Everybody here (on San Domino), if they weren’t prisoners they were military officers, and the only people who weren’t military officers were my family. At that time there couldn’t be any connection between the two islands after 10 o’clock, except for my family who could go back and forth. Life happened on San Nicola rather than San Domino at that time.

‘Twice a day on San Domino and on San Nicola there was an assembly point in the square, and the police was there, and they had to call out all the names of the prisoners and they had to state their presence. It depended, there were about 10 or 15 people who would go to San Nicola every day for all sorts of reasons, people who had to go the police headquarters to pick up documents or whatever it was they needed to do, so every day they were free to go to San Nicola as they pleased.’

A commendation awarded to Attilio’s father by Sandro Pertini, president of the Republic

‘He would still defend anybody who had been sent to prison here’

Attilio remembers many of the prisoners and their individual stories. For example: ‘there was a building close by with a singer who’d become a little bit famous because he’d written this song, and every night at midnight he would sing this song.’

There were often famous names in politics, too.

‘There was Mussolini’s secretary in the next building here. He’d argued with Mussolini and Mussolini had him sent here. He was here with two manservants; he was very friendly with them and they were always together.

‘Sandro Pertini was exiled here for 12 days. He was very much against fascism. After he left he gave my father a present.’

Sandro Pertini, who had gone on to become President of the Republic, had awarded Attilio’s father a commendation of thanks. Attilio says his father was known for treating prisoners on the islands well.

‘He sent home about ten guards and about ten police officers because they were unkind to the prisoners.

‘Right until the end, if it wasn’t the prisoners themselves, it was the sons and daughters of the prisoners who would come to see my father and say thank you for the way he treated them. Because although he was a fascist he would still defend anybody who had been sent to prison here, who had been exiled here for their political beliefs against Mussolini.’

At work in the fields (Photo: Attilio Carducci)

Daily life

On San Domino, prisoners were able to move around the island freely, except at night. During the day, many of them worked alongside Attilio and his family.

‘Every morning I would have about 30 or 40 of the prisoners working for me on the farm, with the animals, the crops in the fields…They were paid according to whatever task they did.’

As well as prisoners, daily life involved encountering the soldiers who had been sent to the islands to guard them.

‘They sent the Alpinis here. The main headquarters were on San Nicola but the headquarters of the Alpini were here. At the time there weren’t any phones or means of communication like today, and nobody could circulate after 10 o’clock - everybody, not just the prisoners, had to be indoors - except me, I could go from one island to another. My task was to bring the special word to the Alpini which would give them permission to operate or do whatever they needed to do.’

The ‘fascist saturday’ on San Nicola. The man in white may be Coviello. Source: ‘La Citta e L’Isola’ by Gianfranco Goretti and Tommaso Giartosio

The commander of the Tremiti Island prisons was a man named Francesco Coviello. I first came across his name as part of my research, and found a grainy black and white photograph in the book which was my main secondary source, ‘La Citta e L’Isola.’ When I showed Attilio this photograph and mentioned Coviello’s name, he recognised both.

‘At first he [Coviello] was on San Nicola but people on San Domino depended on him as well. They sent him away from the Tremitis for a year, then he came back.

‘Everybody really loved him, because he was a very rigorous kind of person, everyone thought very highly of him.’

The ‘arrusi’

WATCH: A video clip from my interview with Attilio Carducci, on the ‘arrusi’

The Catanian prisoners who were the inspiration for Mussolini’s Island - the ‘arrusi’ - were brought to San Domino in 1939.

‘I was about twelve or thirteen years old’ Attilio says. ‘I can remember them very well. They were where the current hotel San Domino is - that’s where they were kept.

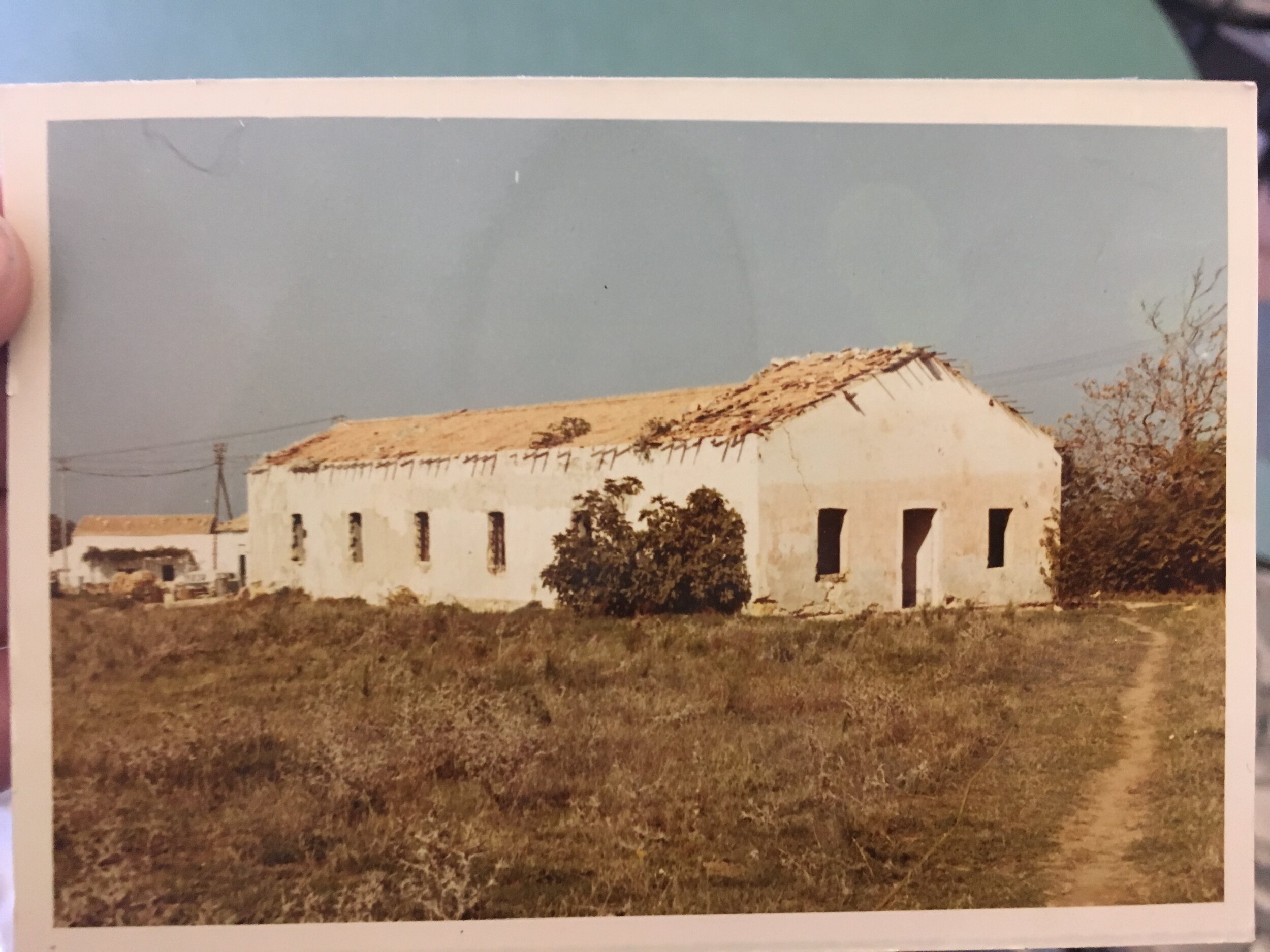

Below: The hotel San Domino, and a photograph of its original building, where the prisoners were housed

“The building was made in such a way that there were these two corridors, at the end of which were two apartments. And in the corridors were all the dormitories for these gay prisoners, and in the two apartments there was the police.

‘There were these two holes in the doors from which you could see what was happening in the corridors. These prisoners always used to have these parties, in one corridor they would be dressed up as women and in the other they would be dressed up as men. They all had female names, and I used to play pranks on them…’

The pranks involved shooting at the prisoners with airguns - although the ‘bullets’ employed were pieces of rolled up newspaper.

‘They used to have a shop, it was the grocery store. And they would go there and do their shopping and there were about 20 or 30 of them. They would work in my father’s farm with the livestock.

‘At the time they seemed happy enough. They had the obligation though to be indoors by eight o’clock. They didn’t get locked in but they were requested to be indoors by eight o’clock. The prisoners who would be working in the fields or in the farm or wherever, they had permits so that they could go back out later, whether it was half past eight or nine o’clock.

‘Every morning they used to get a salary of four lira, whereas the prisoners who were in prison because of political beliefs, for being against fascism, they got five lira every morning.”

‘One day I went to the headquarters and there was nobody there’

Image: Attilio Carducci

A lot of the sources I used for my research mention anecdotal reports of the prisoners being sad to return home, after their year on San Domino. Attilio says he didn’t remember whether this was the case - he was just a child at the time.

‘I remember that the younger ones, when they left, were recruited as soldiers in wars elsewhere.’

What Attilio remembers most is the impact the prisoners’ departure had on him and his family.

‘Every morning I would go to the headquarters and they would give me however many people were needed as workforce, and then one day I went to the headquarters and there was nobody there, because these three big ships had come to pick up all the prisoners and take them away.

‘And so I was left all by myself, and I had to milk the cows, make the cheese, pick fruits and vegetables by myself. There were only about seven or eight prisoners left on the island, so I had to ask the locals to give me a hand. There was nobody willing to come from outside to the Tremitis, so we were starving.

‘My father moved to Foggia. We would come and go, but we always had to come back because we had the animals here. At least there were ten of us children, so we were plenty of people!’

Although most prisoners left the island after the term of their imprisonment was over, Attilio says some remained. Some of their descendants even, he told me, still live on the island today, living side by side with those whose families were born on the Tremiti Islands.

Witnesses to history

At the end of one of our conversations, we pause for a moment, sipping on the nut wine which Attilio makes himself (which I suspect might be far stronger than it tastes!) I turn to look at the street behind us; the quiet, low roofed houses, the restaurants and bars, and try to imagine this place as anything but a peaceful, quiet residential street on a tiny island frequented by Italian holidaymakers, who come here for scuba diving, boating and family activities.

‘I put the first brick in one of those houses’ Attilio says, pointing. ‘When I was very small.’

These are the same houses which his father, Vincenzo, had worked hard to have built, and which had once been part of a project to encourage Italian families to move to the Tremiti Islands. It never quite happened - today, the population of the islands is less than 500, most of whom, as in the past, live on San Nicola. It’s amazing to think that, despite their quiet, peaceful seclusion, the islands have been witnesses to such a dramatic period of history - even more amazing to be able to hear some of that history first hand.

Attilio Carducci (far right) with his family (Photo: Attilio Carducci)

I’m extremely grateful to Attilio Carducci for sharing his memories with me, as well as his amazing family photographs. Huge thanks also to Vivien Williams, who acted as interpreter for our conversations. (Any errors or misinterpretations are entirely mine!)